At a time of political stress in Germany, the Bauhaus– probably among the most prominent architecture, art and style schools worldwide– has actually ended up being the target of reactionary attacks.

Hans-Thomas Tillschneider, a member of the reactionary Option for Germany (AfD) and a member of the local parliament of Saxony-Anhalt in eastern Germany, has actually blamed his location’s financial issues on Bauhaus modernism.

His not likely medical diagnosis can be found in action to the local conservative CDU federal government’s “believe modern-day” project, which looks for to bring in financial investment into the location and mentions the Bauhaus motion as an example of in your area grown quality.

Tillschneider asserts that for the location’s financial stagnancy to be fixed “we do not require to believe modern-day, we require to believe conservatively.” He declines Bauhaus concepts as diffused with communist ideology. With these attacks, Tillschneider has actually begun a quasi-re-enactment of a historic culture war over German nationwide identity and social stress and anxieties.

Established in 1919 by designer Walter Gropius in the German city of Weimar, the Bauhaus and its personnel shared a program of product utopianism. This was revealed by means of an explorative workshop idea that left from standard modes of mentor.

Such progressive practices moved the Bauhaus politically to the left, which would make it susceptible to ideological attack throughout the Weimar republic, Germany’s very first (and stopped working) democracy.

In the controversial argument about nationwide identity that followed completion of the monarchy in 1918, Bauhaus artists occupied an uneasy position in between 2 schools of idea amongst the informed elite.

One side had actually opened to modern-day aesthetic appeals (such as impressionism and expressionism). The other– the conservatives– rather accepted a creative nationalism that had actually manifested with German marriage in 1871.

They saw “real art” as originating from individuals and in turn informing them as devoted residents. Visually, conservatives discovered these worths revealed in Weimar classicism. Strangely enough, provided the focus on art by the individuals, this was a rather special, high-brow type of literature, theatre and visual arts.

Bauhaus concepts, rather, were anti-bourgeois, progressive and speculative, while at the exact same time postulating the value of developing art for everybody to gain access to and delight in. Such democratisation of design, nevertheless, was tough to attain, and the majority of what the Bauhaus produced stayed unaffordable to the masses. However, these clashing visions politicised culture throughout the interwar years.

In 1925, the school needed to move from Weimar to Dessau (in Saxony-Anhalt) after it lost its financing. This was the fallout of a disagreement with the conservative political celebrations that ruled the city at the time.

In Dessau, the Bauhaus instructors constructed a school structure that followed their modern-day visual concepts. In spite of duplicated efforts by Gropius to depoliticise the Bauhaus by indicating its visual pluralism, internal arguments about the location of architecture in society and politics continued.

The point of contention was the idea of “New Neutrality” (Neue Sachlichkeit) which discovered expression in Neues Bauen: modularised building and construction which presented the industrialised pre-fabrication of structure parts in a turn away from standard crafts.

Ultimately, Gropius left the Bauhaus and in his location came the freely socialist designer Hannes Meyer. After taking control of as director in 1928, he repoliticised the school and moved it back to the left.

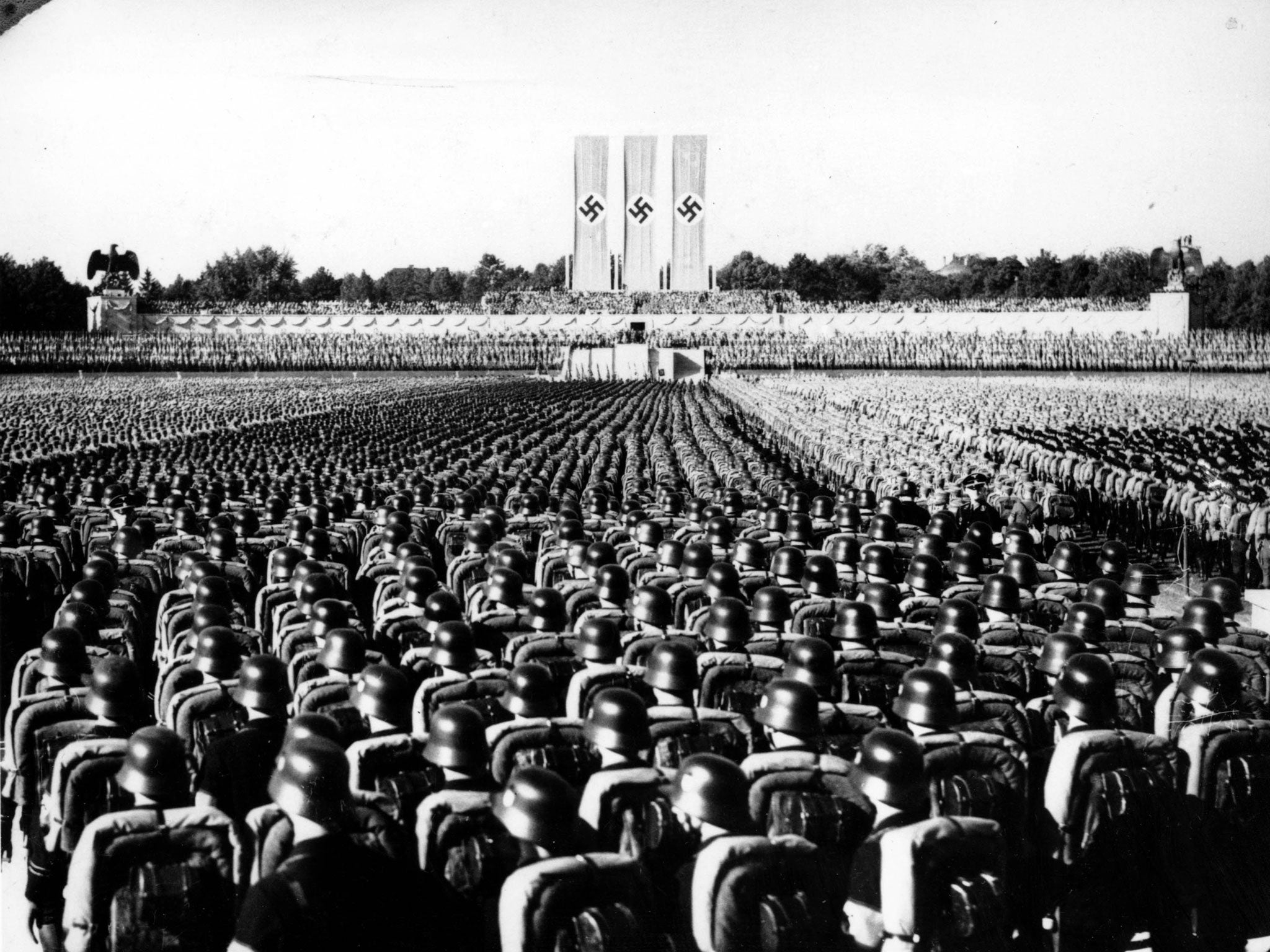

In the heated political environment of the late Weimar republic, the Bauhaus experienced a brand-new existential danger. When the Nazis took control of in regional elections in 1931, they asked for the damage of the Bauhaus school.

The Bauhaus moved once again in 1932, this time to Berlin, where it continued as a personal organization to prevent restored dispute with the ever more effective Nazis. However, when Adolf Hitler took power in early 1933, the school and its personnel ended up being victims of the Nazis’ anti-socialist procedures.

The Bauhaus school closed on July 20 1933 and its personnel distributed, frequently to far locations. Lots of went to the United States, where they continued in the tradition of the “Bauhaus spirit” by signing up with the global modernism motion that ended up being the specifying Western visual in the 1950s.

Although the creative impacts and expressions had actually stayed varied throughout the life time of the school, postwar discourse has structured it to basic geometric shapes, a choice for the colours white, blue, red and yellow, and a focus on horizontal lines and viewpoints.

The Nazis had actually identified Bauhaus aesthetic appeals as “degenerate”. In the cold war period, the socialist East German federal government called out Bauhaus modernism and its disciples as cosmopolitan in the pejorative sense.

They were implicated of deserting German nationwide heritage for the sake of global “formalism”, raising type– as referring to work– over cultural material. Tillschneider has actually put it much more provocatively: “They rejected guy’s connection to land and his cultural roots”. While a big interpretative overstretch, these declarations do not come as a surprise.

This year marks the centennial of the relocate to Dessau, where the school structure still stands happily as a Unesco world heritage website. Tillschneider utilized this minute to perpetuate the culture war that the AfD has actually ended up being understood for over the previous years.

He is corresponding the CDU to an oversimplified representation of the Bauhaus tradition– one that is anti-crafts, anti-bourgeois and internationalist– he indicates his political competitors protest German custom and culture. These are the nativist beliefs that sustain the AfD. It is a method of low-cost wins at the expenditure of the electorate’s stress and anxieties about Germany’s cultural and nationwide identity.

Karin Schreiter is a Senior Speaker in German and History at King’s College London

This post is republished from The Discussion under an Innovative Commons licence. Check out the initial post