The US military’s robotic mini-space shuttle dropped out of orbit and glided to a runway in California late Thursday, ending a 434-day mission that pioneered new ways of maneuvering in space.

The X-37B spaceplane touched down on Runway 12 at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, at 11:22 pm local time Thursday (2:22 am EST Friday), capping its high-flying mission with an automated reentry and landing on the nearly three-mile-long runway at the West Coast’s spaceport.

The Space Force did not publicize the spacecraft’s return ahead of time, keeping with the Pentagon’s policy of secrecy surrounding the X-37B program. This was the seventh flight of an X-37B spaceplane, or Orbital Test Vehicle, since its first foray into orbit in 2010.

Classified, but not invisible

The winged spaceship launched on December 28, 2023, into an elliptical, or oval-shaped orbit taking the X-37B thousands of miles from Earth. The Space Force did not disclose the exact parameters of the spaceplane’s orbit, but a few months after the launch, amateur observers on the ground detected the X-37B in an orbit ranging between 201 and 24,133 miles in altitude (323 and 38,838 kilometers). The orbit was inclined about 59 degrees to the equator.

The first six X-37B missions launched on smaller rockets, limiting their range to low-Earth orbit. For the seventh mission, the Space Force selected SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket, which had the extra oomph to boost the spaceplane to greater distances.

Since the first X-37B flight in 2010, defense officials across multiple administrations have hesitated to release details about the goals of each mission. In broad terms, military officials describe the X-37B as a platform for technology demonstration experiments. With rare exceptions, the Pentagon has declined to release the specifics of those experiments, other than highlighting the benefits of putting a payload into space and returning it to Earth intact, something the X-37B is uniquely able to do.

This policy largely remained in place for the seventh X-37B mission, although there were a few disclosures that shed new light on the spaceplane’s capabilities.

In October, the Space Force announced the X-37B began a series of “aerobraking” maneuvers to dip its stubby wings into the uppermost reaches of the atmosphere at each perigee, or the lowest point of each of its orbits around the Earth. Over time, these encounters with the diffuse gases in the upper atmosphere gradually slowed the X-37B’s velocity through aerodynamic drag, bringing its orbit closer to the planet.

Aerobraking is a fuel-efficient means of changing a spacecraft’s orbit. NASA has used a similar approach to reposition satellites in orbit around Mars without expending too much fuel. This is the first time the Space Force has said it used aerobraking on one of its missions.

“Mission 7 broke new ground by showcasing the X-37B’s ability to flexibly accomplish its test and experimentation objectives across orbital regimes,” said Gen. Chance Saltzman, the Space Force’s chief of space operations, in a statement. “The successful execution of the aerobraking maneuver underscores the US Space Force’s commitment to pushing the bounds of novel space operations in a safe and responsible manner.”

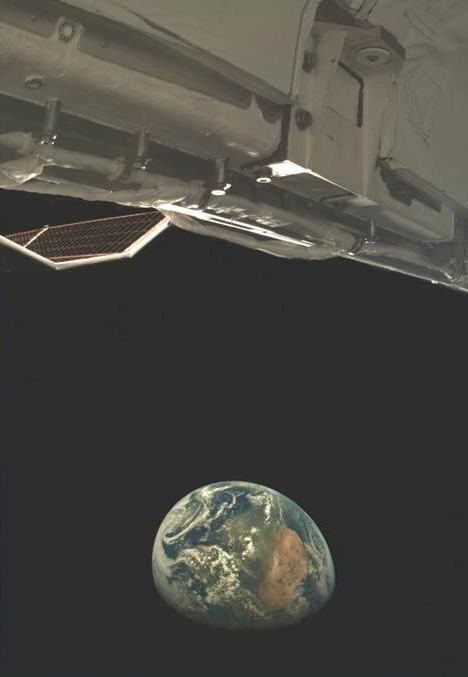

The military has two reusable Boeing-built X-37Bs in its inventory. The vehicles measure about 29 feet (9 meters) long, roughly one-quarter the length of one of NASA’s space shuttle orbiters. The X-37B has a wingspan just shy of 15 feet (4.6 meters), and is not designed to carry people. In orbit, the spaceplane opens the doors to its cargo bay and extends a solar panel to produce electricity, allowing the X-37B to loiter in orbit for years.

The aerobraking maneuver also allowed ground controllers to dispose of the X-37B’s service module, an add-on mounted to the rear of the spacecraft, without stranding it in a high orbit where it could pose a risk as space junk for decades or centuries.

On this mission, military officials said the X-37B tested “space domain awareness technology experiments” that aim to improve the Space Force’s knowledge of the space environment. Defense officials consider the space domain—like land, sea, and air—a contested environment that could become a battlefield in future conflicts.

The Space Force hasn’t announced plans for the next X-37B mission. Typically, the next X-37B flight has launched within a year of the prior mission’s landing. So far, all of the X-37B flights have launched from Florida, with landings at Vandenberg and at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, where Boeing and the Space Force refurbish the spaceplanes between missions.

The aerobraking maneuvers demonstrated by the X-37B could find applications on future operational military satellites, according to Gen. Stephen Whiting, head of US Space Command.

“The X-37 is a test and experimentation platform, but that aerobraking maneuver allowed it to bridge multiple orbital regimes, and we think this is exactly the kind of maneuverability we’d like to see in future systems, which will unlock a whole new series of operational concepts,” Whiting said in December at the Space Force Association’s Spacepower Conference.

Space Command’s “astrographic” area of responsibility (AOR) starts at the top of Earth’s atmosphere and extends to the Moon and beyond.

“An irony of the space domain is that everything in our AOR is in motion, but rarely do we use maneuver as a way to gain positional advantage,” Whiting said. “We believe at US Space Command it is vital, given the threats we now see in novel orbits that are hard for us to get to, as well as the fact that the Chinese have been testing on-orbit refueling capability, that we need some kind of sustained space maneuver.”

Improvements in maneuverability would have benefits in surveilling an adversary’s satellites, as well as in defensive and offensive combat operations in orbit.

The Space Force could attain the capability for sustained maneuvers—known in some quarters as dynamic space operations—in several ways. One is to utilize in-orbit refueling that allows satellites to “maneuver without regret,” and another is to pursue more fuel-efficient means of changing orbits, such as aerobraking or solar-electric propulsion.

Then, Whiting said Space Command could transform how it operates by employing “maneuver warfare” as the Army, Navy and Air Force do. “We think we need to move toward a joint function of true maneuver advantage in space.”