It’s a regrettable reality that there is never time to cover all the interesting scientific stories we come across each month. In the past, we’ve featured year-end roundups of cool science stories we (almost) missed. This year, we’re experimenting with a monthly collection. February’s list includes dancing sea turtles, the secret to a perfectly boiled egg, the latest breakthrough in deciphering the Herculaneum scrolls, the discovery of an Egyptian pharaoh’s tomb, and more.

Dancing sea turtles

There is growing evidence that certain migratory animal species (turtles, birds, some species of fish) are able to exploit the Earth’s magnetic field for navigation, using it both as a compass to determine direction and as a kind of “map” to track their geographical position while migrating. A paper published in the journal Nature offers evidence of a possible mechanism for this unusual ability, at least in loggerhead sea turtles, who perform an energetic “dance” when they follow magnetic fields to a tasty snack.

Sea turtles make impressive 8,000-mile migrations across oceans and tend to return to the same feeding and nesting sites. The authors believe they achieve this through their ability to remember the magnetic signature of those areas and store them in a mental map. To test that hypothesis, the scientists placed juvenile sea turtles into two large tanks of water outfitted with large coils to create magnetic signatures at specific locations within the tanks. One tank features such a location that had food; the other had a similar location without food.

They found that the sea turtles in the first tank performed distinctive “dancing” moves when they arrived at the area associated with food: tilting their bodies, dog-paddling, spinning in place, or raising their head near or above the surface of the water. When they ran a second experiment using different radio frequencies, they found that the change interfered with the turtles’ internal compass, and they could not orient themselves while swimming. The authors concluded that this is compelling evidence that the sea turtles can distinguish between magnetic fields, possibly relying on complex chemical reactions, i.e., “magnetoreception.” The map sense, however, likely relies on a different mechanism.

Nature, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08554-y (About DOIs).

Long-lost tomb of Thutmose II

Thutmose II was the fourth pharaoh of the Tutankhamun (18th) dynasty. He reigned only about 13 years and married his half-sister Hatshepsut (who went on to become the sixth pharaoh in the dynasty). Archaeologists have now confirmed that a tomb built underneath a waterfall in the mountains in Luxor and discovered in 2022 is the final resting place of Thutmose II. It’s the last of the 18th dynasty royal tombs to be found, more than a century after Tutankhamun’s tomb was found in 1922.

When it was first found, archaeologists thought the tomb might be that of a king’s wife, given its close proximity to Hatshepsut’s tomb and those of the wives of Thutmose III. But they found fragments of alabaster vases inscribed with Thutmose II’s name, along with scraps of religious burial texts and plaster fragments on the partially intact ceiling with traces of blue paint and yellow stars—typically only found in kings’ tombs. Something crucial was missing, however: the actual mummy and grave goods of Thutmose II.

It’s long been assumed that the king’s mummy was discovered in the 19th century at another site called Deir el-Bahari. But archaeologist Piers Litherland, who headed the British team that discovered the tomb, thinks that identification was in error. An inscription stated that Hatshepsut had the tomb’s contents relocated due to flooding. Litherland believes the pharaoh’s actual mummy is buried in a second tomb. Confirmation (or not) of his hypothesis won’t come until after archaeologists finish excavating what he thinks is the site of that second tomb, which is currently buried under multiple layers of rock and plaster.

Hidden images in Pollock paintings

Physicists have long been fascinated by the drip paintings of “splatter master” Jackson Pollock, pondering the presence of fractal patterns (or lack thereof), as well as the presence of curls and coils in his work and whether the artist deliberately exploited a well-known fluid dynamics effect to achieve them—or deliberately avoided them. Now psychiatrists are getting into the game, arguing in a paper published in CNS Spectrums that Pollock—known to incorporate images into his early pre-drip paintings—also used many of the same images repeatedly in his later abstract drip paintings.

People have long claimed to see images in those drip paintings, but the phenomenon is usually dismissed by art critics as a trick of human perception, much like the fractal edges of Rorschach ink blots can fool the eye and mind. The authors of this latest paper analyzed Pollock’s early painting “Troubled Queen” and found multiple images incorporated into the painting, which they believe establishes a basis for their argument that Pollock also incorporated such images into his later drip painting, albeit possibly subconsciously.

“Seeing an image once in a drip painting could be random,” said co-author Stephen M. Stahl of the University of California, San Diego. “Seeing the same image twice in different paintings could be a coincidence. Seeing it three or more times—as is the case for booze bottles, monkeys and gorillas, elephants, and many other subjects and objects in Pollock’s paintings—makes those images very unlikely to be randomly provoked perceptions without any basis in reality.”

CNS Spectrums, 2025. DOI: 10.1017/S1092852924001470

Solving a fluid dynamics mystery

Every fall, the American Physical Society exhibits a Gallery of Fluid Motion, which recognizes the innate artistry of images and videos derived from fluid dynamics research. Several years ago, physicists at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) submitted an entry featuring a pool of red dye, propelled by a few drops of soap acting as a surfactant, that seemed to “know” how to solve a maze whose corridors were filled with milk. This is unusual since one would expect the dye to diffuse more uniformly. The team has now solved that puzzle, according to a paper published in Physical Review Letters.

The key factor is surface tension, specifically a phenomenon known as the Marangoni effect, which also drives the “coffee ring effect” and the “tears of wine” phenomenon. If you spread a thin film of water on your kitchen counter and place a single drop of alcohol in the center, you’ll see the water flow outward, away from the alcohol. The difference in their alcohol concentrations creates a surface tension gradient, driving the flow.

In the case of the UCSB experiment, the soap reduces local surface tension around the red dye to set the dye in motion. There are also already surfactants in the milk that work in combination with the soapy surfactant to “solve” the maze. The milk surfactants create varying points of resistance as the dye makes its way through the maze. A dead end or a small space will have more resistance, redirecting the dye toward routes with less resistance—and ultimately to the maze’s exit. “That means the added surfactant instantly knows the layout of the maze,” said co-author Paolo Luzzatto-Fegiz.

Physical Review Letters, 2025. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1802831115

How to cook a perfectly boiled egg

There’s more than one way to boil an egg, whether one likes it hard-boiled, soft-boiled, or somewhere in between. The challenge is that eggs have what physicists call a “two-phase” structure: The yolk cooks at 65° Celsius, while the white (albumen) cooks at 85° Celsius. This often results in overcooked yolks or undercooked whites when conventional methods are used. Physicists at the Italian National Research Council think they’ve cracked the case: The perfectly cooked egg is best achieved via a painstaking process called “periodic cooking,” according to a paper in the journal Communications Engineering.

They started with a few fluid dynamics simulations to develop a method and then tested that method in the laboratory. The process involves transferring a cooking egg every two minutes—for 32 minutes—between a pot of boiling water (100° Celsius) and a bowl of cold water (30° Celsius). They compared their periodically cooked eggs with traditionally prepared hard-boiled and soft-boiled eggs, as well as eggs prepared using sous vide. The periodically cooked eggs ended up with soft yolks (typical of sous vide eggs) and a solidified egg white with a consistency between sous vide and soft-boiled eggs. Chemical analysis showed the periodically cooked eggs also contained more healthy polyphenols. “Periodic cooking clearly stood out as the most advantageous cooking method in terms of egg nutritional content,” the authors concluded.

Communications Engineering, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s44172-024-00334-w

More progress on deciphering Herculaneum scrolls

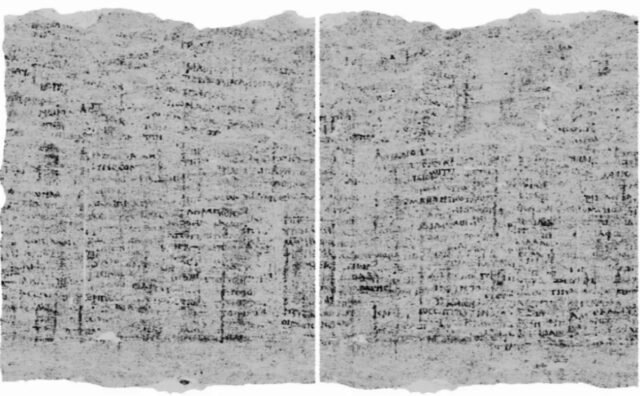

The Vesuvius Challenge is an ongoing project that employs “digital unwrapping” and crowd-sourced machine learning to decipher the first letters from previously unreadable ancient scrolls found in an ancient Roman villa at Herculaneum. The 660-plus scrolls stayed buried under volcanic mud until they were excavated in the 1700s from a single room that archaeologists believe held the personal working library of an Epicurean philosopher named Philodemus. The badly singed, rolled-up scrolls were so fragile that it was long believed they would never be readable, as even touching them could cause them to crumble.

In 2023, the Vesuvius Challenge made its first award for deciphering the first letters, and last year, the project awarded the grand prize of $700,000 for producing the first readable text. The latest breakthrough is the successful generation of the first X-ray image of the inside of a scroll (PHerc. 172) housed in Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries—a collaboration with the Vesuvius Challenge. The scroll’s ink has a unique chemical composition, possibly containing lead, which means it shows up more clearly in X-ray scans than other Herculaneum scrolls that have been scanned.

The machine learning aspect of this latest breakthrough focused primarily on detecting the presence of ink, not deciphering the characters or text. Oxford scholars are currently working to interpret the text. The first word to be translated was the Greek word for “disgust,” which appears twice in nearby columns of text. Meanwhile, the Vesuvius Challenge collaborators continue to work to further refine the image to make the characters even more legible and hope to digitally “unroll” the scroll all the way to the end, where the text likely indicates the title of the work.

What ancient Egyptian mummies smell like

Much of what we know about ancient Egyptian embalming methods for mummification comes from ancient texts, but there are very few details about the specific spices, oils, resins, and other ingredients used. Science can help tease out the secret ingredients. For instance, a 2018 study analyzed organic residues from a mummy’s wrappings with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and found that the wrappings were saturated with a mixture of plant oil, an aromatic plant extract, a gum or sugar, and heated conifer resin. Researchers at University College London have now identified the distinctive smells associated with Egyptian mummies—predominantly”woody,” “spicy,” and “sweet,” according to a paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

The team coupled gas chromatography with mass spectrometry to measure chemical molecules emitted by nine mummified bodies on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and then asked a panel of trained human “sniffers” to describe the samples smells, rating them by quality, intensity, and pleasantness. This enabled them to identify whether a given odor molecule came from the mummy itself, conservation products, pesticides, or the body’s natural deterioration. The work offers additional clues into the materials used in mummification, as well as making it possible for the museum to create interactive “smellscapes” in future displays so visitors can experience the scents as well as the sights of ancient Egyptian mummies.

Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2025. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.4c15769