Scientists have long understood that microbes, zooplankton, and fish are vital sources of recycled nitrogen in coastal waters. But whales and other marine mammals like seals also help in this regard by releasing tons of nutrient-rich fecal matter into those waters. Now we can add whale urine to that list, according to a paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

“Lots of people think of plants as the lungs of the planet, taking in carbon dioxide, and expelling oxygen,” said co-author Joe Roman, a biologist at the University of Vermont. “For their part, animals play an important role in moving nutrients. Seabirds transport nitrogen and phosphorus from the ocean to the land in their poop, increasing the density of plants on islands. Animals form the circulatory system of the planet—and whales are the extreme example.”

Back in 2010, Roman co-authored a study in which they examined field measurements and population data to determine that whales and seals could be responsible for replenishing 2.3×104 metric tons of nitrogen per year in the Gulf of Maine alone. Specifically, they feed in deeper waters and then release “flocculent fecal plumes” (i.e., feces) at the surface, serving as a kind of “whale pump” that boosts plankton growth, among other tangible benefits.

For this latest study, Roman and his co-authors looked more closely at whale urine and the possible ecological benefits it provides, distributing key nutrients over thousands of miles during whale migrations. “These coastal areas often have clear waters, a sign of low nitrogen, and many have coral reef ecosystems,” said Roman. “The movement of nitrogen and other nutrients can be important to the growth of phytoplankton, or microscopic algae, and provide food for sharks and other fish and many invertebrates.”

A “great whale conveyor belt”

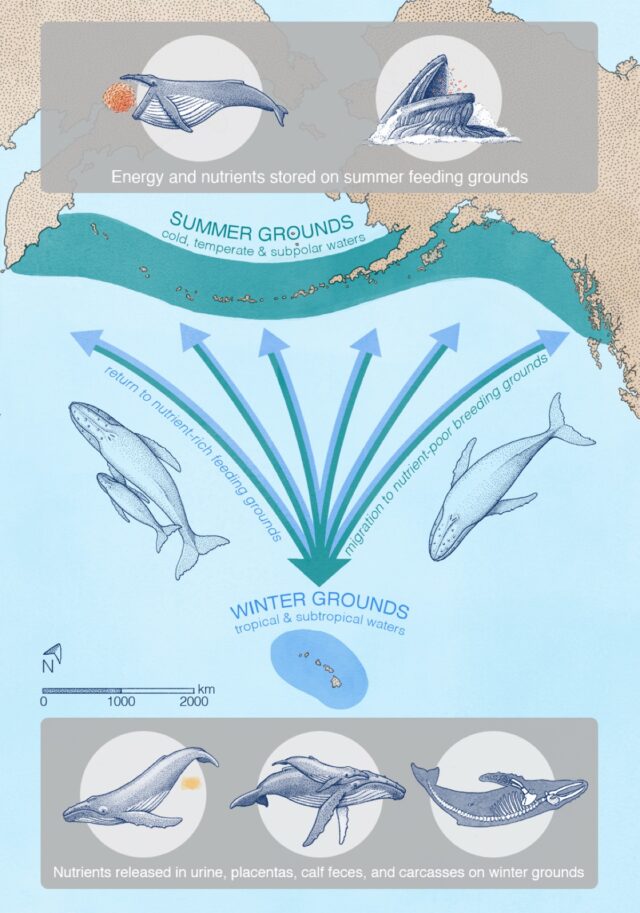

Migrating whales typically gorge in summers at higher latitudes to build up energy reserves to make the long migration to lower latitudes. It’s still unclear exactly why the whales migrate, but it’s likely that pregnant females in particular find it more beneficial to give birth and nurse their young in warm, shallow, sheltered areas—perhaps to protect their offspring from predators like killer whales. Warmer waters also keep the whale calves warm as they gradually develop their insulating layers of blubber. Some scientists think that whales might also migrate to molt their skin in those same warm, shallow waters.

Roman et al. examined publicly available spatial data for whale feeding and breeding grounds, augmented with sightings from airplane and ship surveys to fill in gaps in the data, then fed that data into their models for calculating nutrient transport. They focused on six species known to migrate seasonally over long distances from higher latitudes to lower latitudes: blue whales, fin whales, gray whales, humpback whales, and North Atlantic and southern right whales.

They found that whales can transport some 4,000 tons of nitrogen each year during their migrations, along with 45,000 tons of biomass—and those numbers could have been three times larger in earlier eras before industrial whaling depleted populations. “We call it the ‘great whale conveyor belt,’” Roman said. “It can also be thought of as a funnel, because whales feed over large areas, but they need to be in a relatively confined space to find a mate, breed, and give birth. At first, the calves don’t have the energy to travel long distances like the moms can.” The study did not include any effects from whales releasing feces or sloughing their skin, which would also contribute to the overall nutrient flux.

“Because of their size, whales are able to do things that no other animal does. They’re living life on a different scale,” said co-author Andrew Pershing, an oceanographer at the nonprofit organization Climate Central. “Nutrients are coming in from outside—and not from a river, but by these migrating animals. It’s super-cool, and changes how we think about ecosystems in the ocean. We don’t think of animals other than humans having an impact on a planetary scale, but the whales really do.”

DOI: Nature Communications, 2025. 10.1038/s41467-025-56123-2 (About DOIs).