It was nonetheless darkish on an early January morning in 2024 when Mohammad Ayas slipped out of the world’s largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, and trekked deep into the forest, returning to the place he had fled in 2017. This time, nevertheless, he was not escaping the “raining bullets” that had killed his father – he was going again to coach and battle in opposition to these chargeable for his folks’s bloody exodus from Myanmar.

Ayas, a 25-year-old Rohingya refugee who teaches Burmese to kids within the camps, tells The Unbiased that he and hundreds like him are actually united of their wrestle in opposition to the Myanmar navy and others who stand of their means of “reclaiming their motherland”.

“We’re prepared. I’m able to die for my folks. I don’t care what occurs to me on this battle to reclaim our motherland, our rights and our freedom in Myanmar,” Ayas says.

A whole lot of Rohingya refugees like Ayas are volunteering to affix armed teams having spent years within the Kutupalong refugee camps, the place greater than 1,000,000 members of the persecuted Muslim minority live after fleeing Myanmar, in keeping with refugee accounts and help company stories.

The Unbiased spoke to Rohingya refugees in addition to a person described as their commander within the Cox’s Bazar camps, who mentioned they’re sneaking out for weeks or months at a time to coach with weapons in Myanmar, getting ready to return and battle each the navy junta and any insurgent teams who stand of their means.

Rohingya teams say they’ve been focused in massacres and compelled conscription by each side amid the civil struggle that started following the 2021 coup ousting democratically-elected chief Aung San Suu Kyi and her occasion. One Rohingya recruit advised The Unbiased they hoped the scenario may change if Suu Kyi had been to return to energy – however they had been not keen to attend round for it to occur.

Watch The Unbiased’s documentary Cancelled: The Rise and Fall of Aung San Suu Kyi

Ayas, a father of a four-year-old woman, says he skilled within the jungle for six months, with he and different volunteers transferring their tents to completely different places each few days to keep away from detection. He describes his coaching routine deep within the jungles of Myanmar – that present cowl for rebel actions in addition to non permanent respite for these escaping the brutal civil struggle.

It begins on the first light and recruits are woken up by the sound of a whistle, says Ayas, who attended a six-month coaching programme.

They start with primary health coaching earlier than they’re divided into teams, with some receiving coaching with arms and ammunition and martial arts, whereas others go for technical coaching like dealing with social media, counter-surveillance, or monitoring enemy actions and gathering strategic data.

Within the warmth of the afternoon they bathe, eat and calm down, earlier than the commander leads a second spherical of drills.

Endlessly to Myanmar’s battle, and as situations within the camps worsen, extra Rohingya refugees might discover themselves keen – or pressured – to take up arms.

“Our major aim is peace. We wish to stay peacefully with rights and alternatives in Burma, the place each the federal government and the rebels have taken over our land. We would like our motherland again, and we are going to battle for it,” he says, referring to Myanmar’s colonial-era identify which was modified in 1989.

Ayas, who refused to reveal the identify of the group he’s coaching with in Myanmar, claims: “Greater than 1,000 folks have now joined and are coaching. The recruitment is going on in all places, in all camps.”

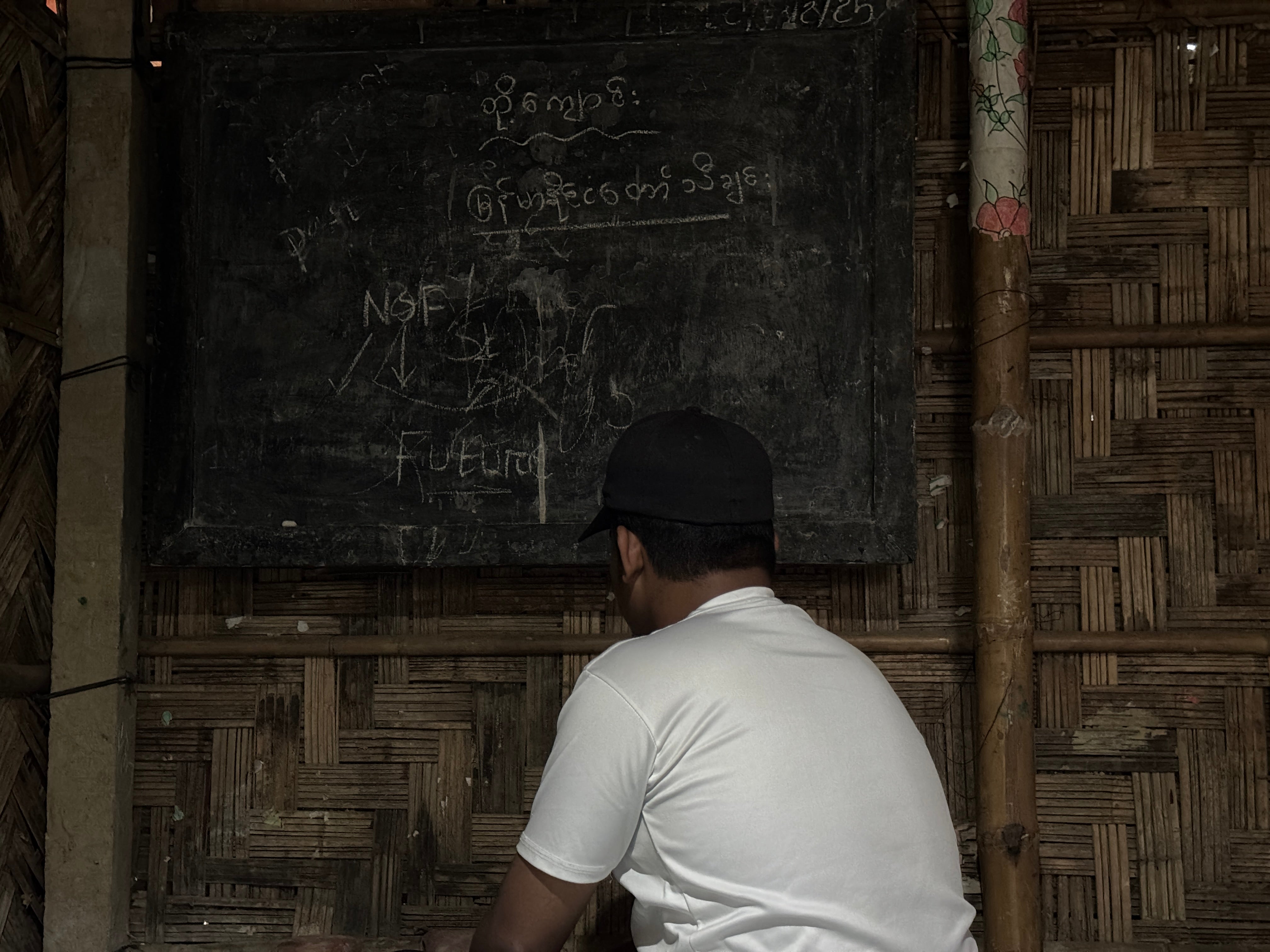

Carrying a cap and tracksuit – in contrast to the vast majority of Rohingya males preferring a easy T-shirt and a longyi or plaid fabric wrapped across the waist – Ayas speaks some English, generally forming damaged sentences.

Ayas fled Myanmar in 2017 when the Myanmar navy, together with Buddhist militias, started what he describes because the coordinated bloodbath of complete Rohingya villages, killing males, ladies, and youngsters alike. The UN has described the violence as a “textbook instance of ethnic cleaning” with stories of girls being raped and whole villages burned down.

A deepening civil struggle between Myanmar’s navy and armed militia teams has meant that Muslim minorities dwelling in Rakhine State have been attacked by each side, forcing them to hunt security in Bangladesh, Malaysia, Singapore, India, and Sri Lanka.

Additionally accused of the systematic persecution of the Rohingya Muslim neighborhood is the Arakan Military (AA), a Buddhist militia group shaped in 2009 that has gained a foothold in Myanmar and now controls virtually all of Rakhine State. The AA claims its goal is to realize larger autonomy and self-determination for the Arakan folks.

Ayas’ household was among the many estimated a million individuals who fled the 2017 navy marketing campaign. However he needed to depart behind his dying father, who was struck by a number of bullets as troopers “started firing randomly at folks”.

“Bullets rained like a monsoon downpour because the navy opened fireplace on folks attempting to flee. The troopers had been butchering our folks,” he recollects, his eyes welling with tears.

Since then, life within the refugee camps has been one in all fixed wrestle, with no future, alternatives, and even primary human rights, he says.

“I’m all the time fascinated by going again dwelling. This isn’t our land, and we don’t wish to stay right here anymore,” he provides.

One other recruit, Abu Niyamat Ulla*, 42, works as a non secular trainer and is affiliated with Islamic Mahaz, a Rohingya Islamist rebel group allied with the bigger Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO).

“Our first enemy is the navy, which is committing genocide on our folks, after which the Arakan Military,” he tells The Unbiased.

Ulla says recruitment efforts have been ongoing within the camps, with males touring to Myanmar for coaching and returning to guide seemingly regular lives within the refugee settlements.

“The commander has directed us to focus on males as younger as 18 or 20 who’re bodily and morally sturdy for recruitment,” he explains.

“We don’t pressure anybody however ask them in the event that they want to return [to Myanmar]. If they’re keen, we information them. The method has already began. Individuals go there for coaching, return, after which others observe,” he says.

Ulla, who remarried after dropping his first spouse and has three kids, says his folks have suffered injustice all their lives whereas the worldwide neighborhood stays centered on wars in Gaza and Ukraine, ignoring the plight of the Rohingya.

He speaks warmly of Suu Kyi’s father Aung San, the independence chief and founding father of Myanmar who “labored with the Rohingya”. “I hope that if Aung San Suu Kyi is launched she may arise for us, although I’m not sure she is going to,” he says.

As a substitute, he says, the Rohingya want to face up for themselves. “The time has come for us to defend our lands, our rights, and reclaim our dignity as human beings,” he asserts.

A maze of slim lanes and alleys in one of many 33 camps results in the safehouse of a person described by recruits as a senior commander spearheading the recruitment drive and coaching efforts. His males mix seamlessly into the crowded refugee camp, indistinguishable from the hundreds of displaced households round them, forming a free perimeter as they led The Unbiased to satisfy him.

No phrases had been exchanged till the commander, a younger man in his mid-30s who gave his identify as Raynaing Soe*, sat cross-legged in an armchair and started talking of his “revolution” to unite the Rohingya neighborhood in opposition to each the navy and the Arakan Military. Soe is a nom de guerre, and he spoke to The Unbiased on situation of anonymity given the sensitivity of his recruitment actions.

“We’d search peaceable reconciliation first, but when that doesn’t occur and our folks proceed to die, then we’re prepared and united to battle for our land,” says Soe, carrying a hat and a T-shirt emblazoned with the phrase “Robust”.

“The entire Rohingya neighborhood has determined to unite. We’re working to carry all folks onto one platform to battle in Rakhine State, to take again our land and our rights.”

Soe says their makes an attempt to cooperate with the AA in opposition to the navy have collapsed a number of occasions since 2021. He refused to reveal his personal group’s affiliation.

“They [the AA] don’t wish to work with the Muslim neighborhood. They solely wish to work for Buddhists. Now, whoever is available in our means – navy or AA – we are going to destroy them to take again our lands.”

Whereas Rohingya recruits within the camp that The Unbiased spoke to denied allegations of pressured conscription, the rights teams and help companies that work to offer inhabitants with their primary humanitarian wants have raised issues over the rise in such drives because the 2021 coup.

There are practically a dozen armed militia teams energetic throughout the camps, in keeping with a report by the ministry of defence in Bangladesh. These teams have been blamed for rampant drug dealing, extortion, killings and human trafficking throughout the camps in addition to inside clashes.

The well-known teams embrace the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO), the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Military (ARSA), the Arakan Rohingya Military (ARA), and Islamic Mahaz.

The RSO has been accused of colluding with the navy in Myanmar and finishing up pressured recruitment of individuals from the camps to battle in opposition to the AA. After gaining a nasty fame for his or her alleged alignment with the junta, the RSO’s members generally go by the choice identify “Maungdaw Militia” to recruit folks.

Fortify Rights director John Quinley says they’ve been investigating Rohingya armed teams for years, gathering testimonies, movies, and audio proof that recruitment – each voluntary and compelled – has been ongoing within the camps.

Quinley says they’ve testimony from Rohingya refugees as younger as 17 years outdated who had been kidnapped from the camp and brought into Myanmar.

“There’s dwindling humanitarian assist within the camps proper now. Below each the [Muhammad] Yunus interim authorities [of Bangladesh] and the previous oppressive authorities of [Sheikh] Hasina, the scenario within the camps has been restrictive. Refugees don’t have any freedom of motion and can’t entry formal schooling in any significant means.

“Each facet of Rohingya folks’s lives stays restricted. Given these situations, many Rohingya have taken issues into their very own palms, looking for to liberate their neighborhood by armed resistance.”

An inside memo by a humanitarian coordination group working in Bangladesh revealed that just about 2,000 folks had been recruited from the refugee camps between March and Could final yr alone, in keeping with a Fortify Rights report.

It mentioned that the drives used strategies resembling “ideological, nationalist and monetary inducements, coupled with false guarantees, threats, and coercion” for recruiting folks.

The Unbiased contacted Bangladesh’s Refugee Aid and Repatriation Commissioner’s Workplace (RRRC), which runs the camps, and the ministry of defence for remark, however has not acquired a response.

Threatening so as to add additional vulnerability and instability into the combo is US president Donald Trump’s blanket govt order halting the work of USAID. That call is anticipated to have a devastating influence on the sprawling refugee camp completely depending on exterior funding – USAID contributed 55 per cent of all overseas help for the Rohingya final yr, in keeping with some estimates.

Quinley says the end result will likely be extra folks turning to armed resistance, except the host authorities in Bangladesh permits them to entry livelihoods or grants them freedom of motion.

“The folks I talked to within the refugee camps have a palpable sense of hopelessness. For a lot of Rohingya, one of many few methods to reclaim company is to say, ‘If I battle, no less than I’ve some management over my destiny.'”

“Until we see actual assist for Rohingya refugees, there may be prone to be an uptick in folks becoming a member of these militant teams – some willingly, however many out of sheer desperation.”

* Names modified to guard id