The Athena spacecraft was not exactly flying blind as it approached the lunar surface one week ago. The software on board did a credible job of recognizing nearby craters, even with elongated shadows over the terrain. However, the lander’s altimeter had failed.

So while Athena knew where it was relative to the surface of the Moon, the lander did not know how far it was above the surface.

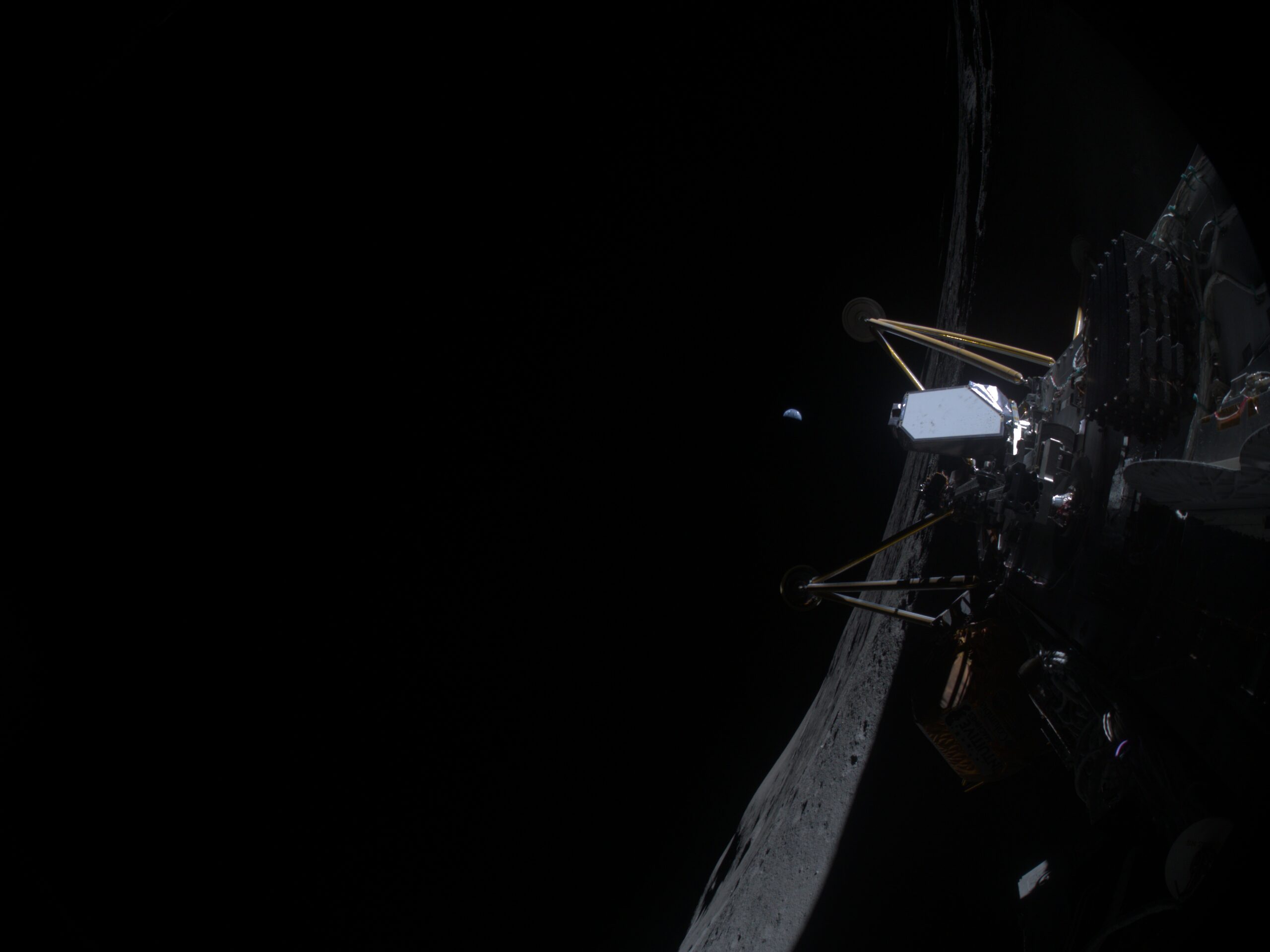

An important detail, that. As a result, the privately built spacecraft struck the lunar surface on a plateau, toppled over, and began to skid across the surface. As it did so, the lander rotated at least once or twice before coming to a stop in a small, shadowed crater.

“The landing was kind of like sliding into second base,” Steve Altemus, chief executive officer of Intuitive Machines, which built the lander, said in an interview Thursday.

Cold and lonely

It has been a busy and tiring week for the chief of a company that seeks to help lead the development of a lunar economy. Expectations were high for this, the company’s second lunar landing attempt after its Odysseus vehicle became the first private spacecraft to ever make a soft landing on the Moon, last year, before toppling over.

In some ways, this mission was even more disappointing. Because Athena skidded across the lunar surface, it dredged up regolith. When it came to a stop, some of this material was blown up into the solar panels—already in a sub-optimal location on its side. The spacecraft’s power reserves, therefore, were limited. Almost immediately, the team at Intuitive Machines knew their spacecraft was dying.

“We knew we had slid into a slightly shadowed crater, and the temperature was very cold,” Altemus said. “The solar arrays had regolith on them, and they weren’t charging, the ones pointing up, enough to give us sufficient power to power the heaters to keep it warm enough to survive.”

The temperature in the crater where Athena ended up was approximately minus 280° Fahrenheit (minus 173° C). With the solar arrays generating only about 100 watts of power, there was not enough energy to both power the spacecraft’s heaters as well as communicate back to Earth using Athena‘s high-gain antenna. So instead of limping along for 50 hours, mission operators decided to operate as robustly as they could for 13 hours, and get down as much data as they could.

During this time the lander was able to accomplish some of its objectives. By landing near the south pole, Athena returned valuable data and imagery to NASA about unexplored vistas. The lander extended NASA’s drill (but did not operate it), private customers, including Nokia and Lonestar Data Holdings, were able to get some useful information from their payloads. But there were also some major disappointments. Lunar Outpost could not deploy its small rover, and an innovative hopper could not be fired up to roam across the Moon.

On balance, it was pretty disappointing, especially considering that Odysseus still did most of it science last year, even on its side.

You go back in, start training again

Yet what Altemus wants people to understand—which he acknowledges is somewhat difficult to explain—is that this mission was largely a success. What can he possibly mean by that?

Compared to the company’s first spacecraft, Athena flew smoothly. During the company’s first lunar flight in 2024, mission operators came into work each shift to put out the fire of the day. By contrast, Athena made it all the way to within miles above the Moon without significant problems. In doing so, the company validated the spacecraft’s methane-based propulsion system, which allows for a “fast” transit to the Moon in less than a week. In addition, the company proved out its communications technology that will be used as part of a lunar data relay network that NASA has contracted with Intuitive Machines to develop. Moreover, Athena attempted to land within a few degrees of the south pole, a challenging location due to the solar angle and uneven terrain, and made it down without crashing.

Of course, the most important thing a lunar lander is supposed to do is land on the Moon, which Intuitive Machines did not do successfully. For the second mission in a row, the lander’s altimeter failed. Although it was a different problem with the spacecraft’s altimeter this time—it’s still unclear why Athena‘s rangefinder failed, perhaps due to a thermal or vibration event—it is frustrating to fail for a similar reason. But all the pieces for success are there, and in the demanding environment of spaceflight, Intuitive Machines is close, Altemus said.

In an effort to buck up the troops, Altemus has been communicating this message to employees over the last week.

“It’s like losing a Final Four game or an NBA title,” he said. “You lose it, and then what do you do? You don’t give up. You go back in, you start training again, you start working out again, and that’s what the team’s doing.”

He said the company is well-capitalized, and already under contract with NASA for two additional landing missions later this decade. It also has the lunar relay network contract valued up to $4.8 billion, and more. The financial runway to achieve Intuitive Machines’ ambitions remains open.

“I would say it’s more disappointing than really a material setback,” Altemus said. “The world was watching, and we put our heart and soul into this company and this vehicle. And I look in the eyes of the team, and they had such ambitions for this mission, Athena and Gracie the hopper. I mean, it was a big leap. It might have been too big a leap on the second mission.”